The Story Behind Boeing's 747 Airborne Aircraft Carrier

In the 1970s, the U.S. Air Force asked Boeing, a leading defense contractor of military aircraft (then and now), to build a bird that could not only carry and launch "micro-fighters" but also retrieve, rearm, and refuel them. The USAF was basically asking for something similar to the fictional Helicarrier used by SHIELD in several Marvel Cinematic Universe movies. But before we dive into that futuristic science-fiction ship, let's take a trip to the past to see what led to even wanting such a machine.

In the early 1900s, the Navy tasked Captain Washington Chambers with finding how these newly developed winged vehicles called planes would impact naval warfare. At this time, it had been less than a decade since the Wright Brothers took to the sky aboard the Wright Flyer I (a chunk of which is now on Mars). This relatively new invention had major naval potential, but in order to test whether planes could be launched from boats, the team would need a pilot. So, Chambers tracked down a man by the name of Eugene Burton Fly for the task.

As a mechanic and race car driver, Ely was a self-taught pilot who had more experience with automobiles. Nevertheless, he showed such aptitude that he soon became part of the Curtiss Exhibition flying team. In 1910, a 50-horsepower Curtiss Pusher aircraft fitted with floats was lifted aboard the USS Birmingham docked in Norfolk, Virginia. The ship maneuvered out to open water, and Ely began his experiment.

[Featured image by Stefanobiondo via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Aircraft carrying ships were tested as early as 1910

The plane didn't so much launch from the deck of the USS Birmingham as it rolled off, hit the water, and bounced (damaging the propeller in the process). Ely somehow managed to keep the plane aloft in the air for 2.5 miles before landing on shore, thus becoming the first person in history to fly a plane off of a ship successfully.

Two months later in January 1911, Ely had a new mission: to land a plane on a ship in the San Francisco Bay. Extra measures were taken for this flight, including the use of the first rudimentary landing arresting system consisting of ropes, sandbags, and a secondary failsafe catch in the form of a canvas awning. Ely took off from a local horse track and landed on the Pennsylvania several minutes later. The arresting system worked exactly as designed, and Ely also became the first person to successfully land a plane onto a ship.

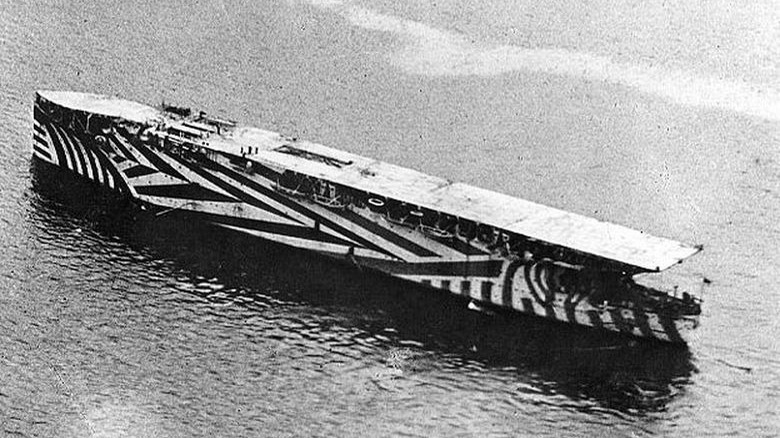

Some other progress toward arming the seas with aircraft was accomplished in the next few years. In 1913, Britain modified one of its light cruisers, the HMS Hermes, into an experimental seaplane carrier. During the thick of World War I in 1916, Germany's fleet of rigid Zeppelin airships acted as long-range reconnaissance craft to track enemy fleet movements. To combat them, the Brits began attaching "flying-off decks" (long, wooden platforms) to their boats so they could get closer to specific targets to launch planes.

The British led the charge for the modern carrier

In 1918, seven Sopwith Camels took off from Britain's HMS Furious, a heavily modified Courageous-class battlecruiser. Their mission was to destroy a pair of Zeppelins housed at a base in Tønder, Denmark (part of Germany at the time). The stakes were high because unlike modern aircraft carriers where planes can both take off and land on flight decks that outstretch multiple football fields, planes back then either had to land on the ground or, if in enemy territory where that wasn't an option, crash in the water as close to the vessel as possible and hope they could be pulled up from the choppy sea.

Germans were shocked by the daring attack because they believed the base was too far away for British planes to reach. Emboldened by their success, the Brits took the hull of a merchant ship and turned it into the first "aircraft carrier" (the HMS Argus), complete with a big flat flight deck. However, World War I ended before it could be used in combat. That stopped exactly no one, as countries around the world immediately recognized the capabilities and potential effectiveness of this new type of ship. The aircraft carrier race was on.

So, back to the 1970s when the U.S. Air Force approached Boeing with what, on the surface, appeared to be a wild and crazy new idea. Except it wasn't exactly a new idea per se.

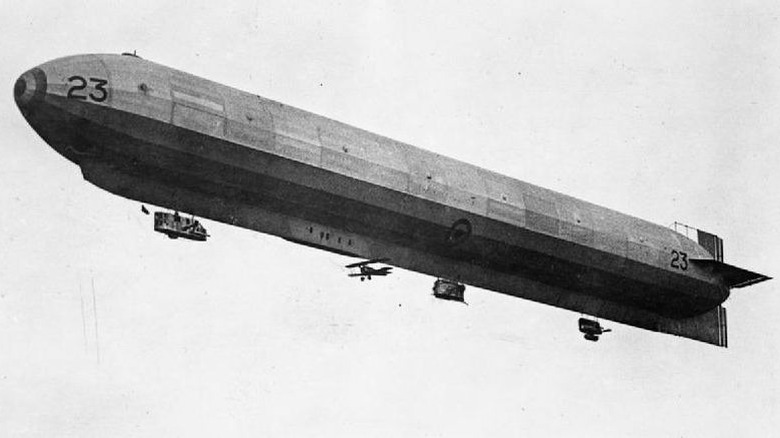

Dirigible balloons were field tested as aircraft carriers

Way back in 1917, the British actually tried using their own dirigible balloons to accomplish such a feat. The HM Airship No. 23 was designed to hold modified Sopwith Camel biplanes that could be carried to a destination and then dropped from underneath. The pilots then fired up the engines and went about their directed mission. Several test flights were made, and the setup worked, but the Brits never moved forward with the plan. Later, during WWII, the Germans tried turning their Graf Zeppelin into an aircraft carrier. Other countries, including the United States (with the Akron-class airship), attempted to perfect an airborne carrier over the years, but nothing came to fruition.

In the 1970s, the USAF, much like the British, was looking for a way to get its aircraft to hard-to-reach targets deep in enemy territory. In this case, the new enemy to watch out for was the Soviet Union. While the big seaworthy carriers worked incredibly well, they were slow and took exponentially longer to get to their desired location than an air-based carrier could. Since the rigid airships hadn't panned out, they turned to something more modern.

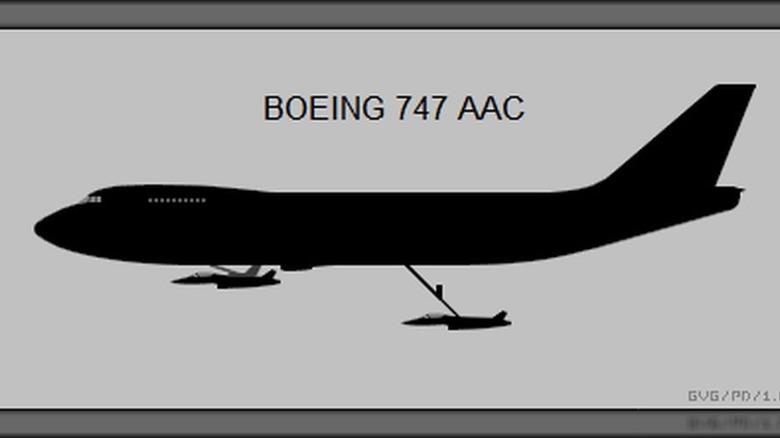

Boeing's big 747-passenger jet made its first flight in 1969, so it was still brand new to the world. After the USAF approached them, Boeing set about working on a design that would convert its much-lauded airplane from carrying hundreds of passengers into one that carried 10 fighter jets.

747s and parasite fighters

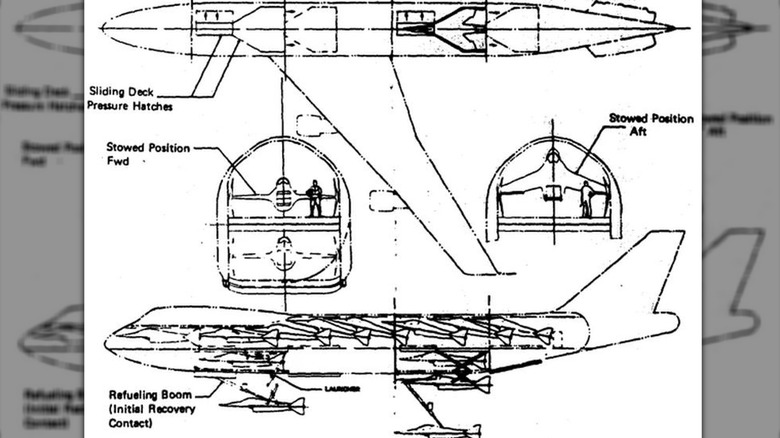

The jets the military had in mind were referred to as parasite fighters, tiny manned "micro-fighters" (designated as Model 985-121) that, in and of themselves, hadn't even been developed yet. In theory, 10 of these 747 airborne aircraft carriers (AAC) could fly 100 of these small fighters into a hot zone, ready for action. By comparison, the USS Gerald R. Ford, one of the biggest ships the world has ever seen, carries approximately 75 aircraft.

The 747 AAC was designed to store these 10 fighters in a stacked formation inside the huge fuselage, then deploy one fighter every 40 seconds using a special conveyor belt and boom deployment system (which was also a new idea). Altogether, the entire "air wing" of 10 fighters could be in the sky within a quarter of an hour. The planes would go about their mission and then be winched back inside for repairs or get rearmed or refueled as needed, giving the fighters an almost unlimited range.

In addition to the 10 micro-fighters, the 747 AAC would carry a crew consisting of 14 fighter pilots, 18 specialists to help with mission logistics, and 12 carrier crew members. However, there were several costly hurdles that needed to be jumped to take this concept from the drawing board to the runaway.

[Featured image by Wikiman264 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Boeing's AAC was technically feasible but obsolete

Once the 747 was ready to go, the scaled-down planes and the rest of the intricate system still didn't exist. Abundant time, money, and resources were needed to create them, but the United States was focused on other things in the '70s, including the Cold War.

While the planes needed to be small, crafting them too tiny could destroy them due to the turbulence created during the docking phase. Additionally, a plane of that size would have to compromise some aspect of its capabilities, such as reduced weapons systems and payloads. As such, those planes wouldn't really stand a chance against any other conventional full-sized fighter they might encounter (like Russia's MiG-25, one of the most iconic fighter jets ever built). Ultimately, the idea for the 747 AAC was abandoned and efforts were funneled into developing the ocean aircraft carriers used today.